Malati Chaudhury: A Biographical Sketch

|

Govt. Of Orissa Activities Report 2004-05 No list of women freedom fighters fighting for India’s independence would be complete without in it the name of Malati Chaudhury. She was born hundred one years ago as Malati (Minu) Sen on 26th July 1904 in a highly anglicised Bengali family.

In no time she emerged as the leader and became affectionate ‘Minu Di’(Minu, the elder sister) for the inmates. These inmates were beholden to her boldness and were convinced that no odd could deter their Minu Di from pursuing her mission. That she was a natural leader was evident in those days according to her contemporary Amita Sen, the mother of Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen. Her compatriots were convinced that she loved to tread uncharted route.

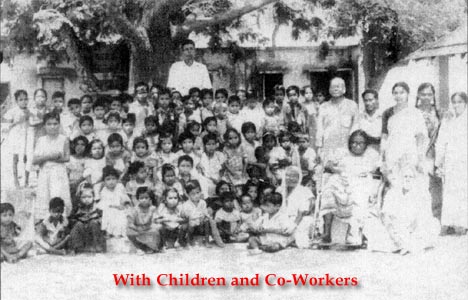

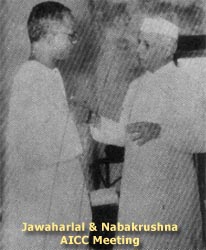

Malati Sen became Malati Chaudhury and began a life consistent with her spirit to tread uncharted route. The couple lived in a village Anakhia, twenty two miles away from Cuttack city, on an ancestral farm of Nabakrushna. In this farm began her active political life. She came in direct contact with the common people and got exposure to the social evil like untouchability prevailing around. A conscious fight against it began with the support of the couple to the consternation of the high caste people of the area. The Chaudhury family which was wholly into the freedom movement provided a unique environment to Malati Devi to give expression, on a wider scale, to the spirit of her rejection of any thing that was foreign. She participated along with other members of the Chaudhury family in protests against the British and was jailed. The British even did not spare her from keeping her separated from her two-year-old first child Uttara (b.1928). In this farm of Anakhia, she was participating in a political formation which was first of its kind in the then India. Under the leadership of Nabakrushna Chaudhury, the Utkal Congress Socialist Workers League was coming into being (February, 1933) to form a cadre of Congress workers believing in socialism under the Marxian influence. Such formation began in Bombay almost a year after (February 1934) under the leadership of Minoo Masani. Bihar, Punjab and a few other states also witnessed such formations subsequently as the support of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru towards such formation within Congress was becoming clear. On 21 & 22 October 1934, the first convention of All India Congress Socialist Party was held. The Utkal Congress socialist Workers League decided to merge itself in this all India Congress Socialist Party and to work as its provincial unit. Consistent with the Marxian principle of abolition of private property, Nabakrushna had handed over this ancestral farm to the League and Malati Devi all her ornaments. These ornaments were sold to publish the weekly organ of the League, SARATHI. Every issue of this magazine in its first page carried the historic message WORKERS OF THE WORLD UNITE. On May 1st, 1933, the Cuttack City witnessed unfamiliar sight of some people marching with slogan WORKERS OF THE WORLD UNITE; the May day was being observed. Malati Devi’s involvement with the common man’s struggle became deeper. She was in a haste to see the elimination of the sufferings of the people. The condition of farmers had moved her. She along with her husband and colleagues of the League began organising the farmers to raise demands, which if met, they believed, would alleviate their sufferings and end their exploitation. The massive gathering of about fifty five thousand farmers on 1st September 1938 in Jenapur of Cuttack district adjacent to Dhenkanal district is remembered as an evidence of Malati Devi’s organisational ability. That she could arouse in people the spirit of sacrifice for freedom from the exploitation was convincingly established when fifty thousand strong mob gheraoed the palace of the king of Dhenkanal against his misrule and oppression. The King fled the palace. But the oppression of the King was replaced by British police repression. It, however, did not deter people from continuing their struggle rather such struggles in other princely states looked forward to the guidance of Malati Devi.

She stood against every kind of superstitions and never hesitated to make scathing criticism of the government even if her husband Nabakrushna Chaudhury led it. Her daring role in uprooting Nepali Baba in Rantalei of Dhenkanal district in 1950-51 is fondly remembered by all rationalists. She had defied her husband's refrain and took on the Baba with only one of her colleagues beside her as against the presence of Baba's numerous devotees. Her protest was so loud that Baba fled the place.

In pursuing her mission of emancipation of common man from various bondage and superstitions and in upholding what is ethical and moral, she always went beyond the constraints of organisation and ideology; as if service to common man was her only ideology and she was steadfast in commitment towards it.

Twenty-five years have elapsed (since independence). Every educated Indian must think as to if we have progressed or regressed. Every educated Indian knows that despite the prevailing democracy based on the adult franchise, we have not progressed, rather regressed. Now, therefore, it is the time when we should find ways towards the well being of our country. I am confident that poor, uneducated and hungry men of this country would find such ways. Only when these people, on realising the country’s situation, prepare a constitution, we shall get a real constitution .The next twenty-seven years till her death, she could increasingly see wreckage of her dream country strewn all around with imperviousness of the elected government pervading all through. Honour and award, though, never held any attraction for her, she was honored with Jamanlal Bajaj award for her service to the downtrodden and contributions to the women and child welfare. But she made history by refusing to receive the award from Rajiv Gandhi, then Prime Minister of India. The Secretary of Jamanlal Bajaj foundation came to Bajirout Chhatrabas and presented her the award in a very simple ceremony. She was bestowed Deshikottam, the highest honour of Viswa Bharati, Shantiniketan, her alma mater on 26th February 1998, and only a fortnight before her death.

They were a rare political couple; the scholarly quietude of Nabakrushna wedded to action packed restlessness of Malati Devi with the singular mission to genuinely empower the poor and down trodden to wrest their claims from the rich and powerful. The problems have not ended. The tribals and downtrodden are still struggling for their existence and remind us the necessity of resurrecting the commitment and boldness of this couple. In contemporary socio-political milieu good examples are under threat of receding from public memory. Not surprisingly, this fate has overtaken the example of Nabakrushna and Malati Chaudhury. This short biographical sketch is an humble attempt to arrest such recession.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Photgraphs : Kasturi Mruga Sama by Manmohan Chaudhury; Numa- A compilation; Smaranika, published by Utkal Navajeevan Mandal; Shradhanjali, published by Bastia Memorial Trust; Adwitiya, published by Nabakrushna Chaudhury Centenary Committee; Ajnanku Abhinandan, published by Banabasi seva Samiti, Baliguda; Ajna by Subhas Chandra Mishra; Pathikrit published by Lohia Academy Trust

Note:

References :