Semiotics of the Orphan in Esan Performance Folktales

Dr. (Mrs) Bridget Inegbeboh Osakue Stevenson Omoera

| Abstract | Introduction |

| Background to the Study | The Nature of Nigerian Folktales about Orphans |

| Findings | Narrative and Stylistic Devices |

| Conclusion | Recommendation |

| References |

Appendix:Esan Folktales |

The orphan in Esan (Nigerian) folktales is a personality that transcends all ages. She/he signifies many phenomena ranging from the scapegoat, the underdog, the metaphysical colossus, the benevolent personality and the king. Man is in the world to communicate and the orphan in tribal folktales communicates many types of behaviour that make it necessary for humanity to really sit back and ponder over who the orphan really is, even in contemporary performance discourse. Therefore, this paper argues that the orphan is more than the hapless fellow we observe on the surface. It uses two Esan performance folktales, The Orphan and the Water-Devils and The Orphan and the Old Woman to ponder over whether mankind abuses the orphan for want of adequate knowledge of her/his various manifestations or what law governs the life of the orphan in Nigerian folktales and what the orphan signifies. It is in an attempt to provide answers to the above questions and others that this study is divided into background, the nature of Nigerian folktales about orphans, thematic concerns of Nigerian tales of orphans, analysis, findings, narrative/stylistic devices and conclusion. In the end, some recommendations are made: that government at various levels, tribal or cultural aficionados should evolve deliberate plans and programmes to address the plight of orphans, that the aesthetics and lessons of Nigerian folktales on orphans should be studied, performed and enjoyed in the different tribal areas of the country and that the orphan should be given assistance to actualise herself/himself and live a psychologically balanced life in the society.

Descriptors: Esan performance folktales, Nigerian people semiotics, orphans, scapegoating, performing artist.

Semiotics (according to Peirce) is, ordinarily speaking, the science of signs. Semiology emphasises that many human actions such as verbal and non-verbal language, our social functions and rituals, our clothes, meals and the very houses we live in communicate meanings which are accepted and shared by members of a particular community or tribal area. These can be analysed and classified as different types of signs in different situations and contexts, using terms from linguistics, the field that studies verbal signs and structures. The major landmarks in this branch of study include the brilliant works of such great minds as: Ferdinand de Saussure, Charles Peirce, Michel Foucault, Umberto Eco, Gerard Genette and Roland Barthes, among others.

These scholars explain sign in different ways. For example, Peirce (1931 – 58) states that a sign or ‘representamen’ is "something which stands to somebody for something". He also states that it is "anything which determines something else (its interpretant) to refer to an object to which itself refers (its object); it stands for something to somebody (its interpretant); and finally it stands for somebody in some respect (ground)." (vol. 2, para 228 and 303). According to Hawkes (1978):

These terms, representamen, object, interpretant and ground can thus be seen to refer to the means by which the sign signifies; the relationship between them determines the precise nature of the process of Semiosis.

It is within this context that this paper elects to follow Peirce’s method. However, it is profitable, for us, to briefly look at who the Esan people are and their location in Nigeria.

Esan People in Brief

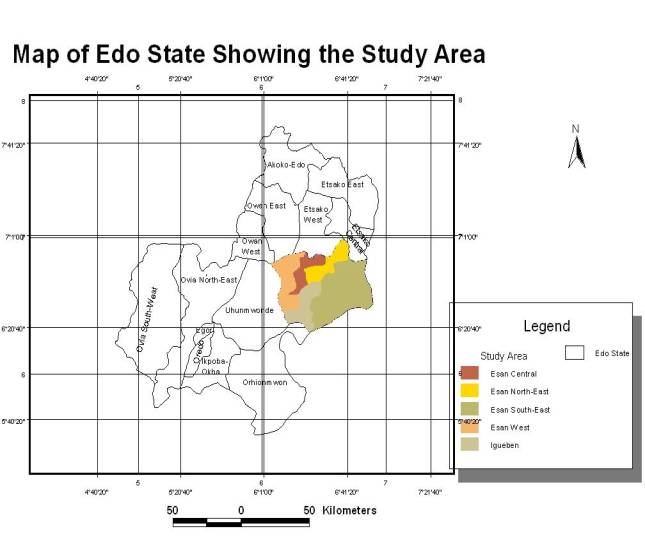

The Esan people in Edo State, South-South of Nigeria, occupy five local government areas. These are: Esan West, Esan North East, Esan South West, Esan Central and Igueben, and are geo-politically known as Edo Central Senatorial District. Figures 1 and 2 are maps showing the Esan speaking area of Edo State and the location of Edo State in Nigeria respectively. The population of the people in this area is 591,534 (Federal Republic of Nigeria Official Gazette, 2009) and they occupy a total landmass of 80.805 square metres (Ewanlen, 2011). Esan turned "Ishan" courtesy of Anglicism, is linked with Benin as an ancestral home (Aluede, 2006). This view is held by Eweka (1992), Okojie (1994) and Egharevba (2005). As a result of its historical origin, the socio-political, socio-cultural and religious structures, including oral folktale traditions, modes of worship and marriage of the people draw on that of the Benin who coronate the reigning sovereigns in this culture area.

Figure 1

Figure 2

The successful understanding of any oral narrative or performance depends on various factors. These include an understanding of the communication system of the custodians of the narratives; a knowledge of the worldview of the people and ability to discern what is meaningful to the people. This is consequent upon the ability to identify the surface of the narrative, as well as the underlying structure with the images and symbols. Stith Thomson in Obuke (1992) contends that tales are made up of motifs. A motif is the smallest element in a tale having the power to persist in a traditional tale. This element must be characteristically striking or unusual and is formed by three categories of folk literature items, viz:

- Actors in a tale, for example, gods or unusual animals or marvellous creatures like witches, fairies, talking animals or some conventional human characters like the youngest child. The cruel stepmother and so on.

- Items in the background of actors which have something unusual or striking, such as magic objects, unusual customs, beliefs, physical phenomenon, strange lands and so on.

- Single independent incidents, that is, strange stories with something memorable.

The orphan features very prominently in many folk stories from Nigerian land. She/he plays major roles and he/she is often at loggerheads with kings, princes, the rich and boastful and death’s chief messenger. Tales about the orphan are very many and interesting. However, there are no known studies on this wonderful and enthralling colossus. She/he is very different from the usual characters in folk literature like the trickster, the youngest child, the cruel stepmother, and so on. She/he is usually a seemingly helpless child/adult who is bereaved of both parents at or shortly after birth. She/he is more than human in folk tales but she/he is neither a spirit nor a god. She/he has some supernatural transformation and dictates the tempo of any tale where she/he appears.

By going through the experiences of orphan in Nigerian oral narratives humanity would learn many lessons on patience, industry, self-reliance and faith, and have a taste of something new in its study of folk literature. There are some known orphans in conventional written literature. They include characters like David Copperfield, Oliver Twist, Huckleberry Fin, Hamlet, Antigone, Snow White, and so on. However, the problem of the orphan in Nigerian oral narratives is handled from a different angle. It is seen from a new light that is peculiarly Nigerian or African. The orphan in Nigerian oral narratives could transcend the present to symbolize the poor, the destitute, the oppressed, the marginalized, the insane people, as well as private houseboys and girls in the present day society. All children are catered for by their parents and society. Where a child has no parents she/he is treated with ignominy. She/he lacks care and food and relies on her/his own personal effort to survive and that is usually an arduous task.

Thus, a successful appreciation of the plight of the orphan involves a comprehensive analysis of the available tales where she/he features. Moreover, a multi-dimensional approach to the study of the orphan tales would have to be adopted to bring out what makes the tales aesthetically relevant. A proper appreciation of the role of the orphan in Nigerian folktales depends on a proper understanding of the meaning of the orphan tales by the audience. However, the lack of proper grasp of the method of analysing tales has been identified as one of the factors hindering the grasping of a fuller import and meaning of tales. Some other factors include the numerous and varied accounts of orphan tales with identical materials, people’s nonchalant attitude to oral narratives and the inability to capture on paper the essence of the actual performance of the folktales.

The Nature of Nigerian Folktales about Orphans

Nigerian folktales normally move from conflict to resolution. There is usually a beginning, middle and an end. Nigerian tales involving the orphan are numerous and varied. They constitute part of the complex communication system of the Nigerian people. This is made up of signs and symbols as well as some structural models. Each tale about the orphan has a new dimension to it each time it is performed. Each performance is unique. Each tale consists of a surface structure, as well as an underlying structure with images and symbols that point to what is meaningful in the life of the Nigerian people.

The surface structure is made up of movements that progress from a conflict situation to a solution, which sometimes gives rise to a bigger conflict and progresses to a final solution, which is usually got in the underworld. This journey marks the climax of the performance, after which a surprising and more desirable resolution is arrived at. Performance of the tales is communal, as different members of the audience present get involved. They throw in their side comments of approval or disapproval following their agreement with the authenticity of the performance and their enjoyment of the occasion.

In a traditionally oriented setting, the audience participates very actively if the members are toned up with shots of alcohol before and during the performance. Some overzealous members take over the narration, particularly when the artist alludes to some other incidents that exemplify some aspects of the narration that is by way of digression. These enthused people supply the required digression. They tell the anecdotes and stop when they have made their point to allow the performing artist carry on with the narration. They sing, gesticulate, clap their hands, drum and dance to some of the narrative renditions.

These people are mostly peasants who easily identify with the orphan and see her/him as a replica of their own lot in life. They see her/him as the epitome of poverty, oppression, injustice and discrimination in the society. In most cases the orphan has cause to explain to an audience the cause of all her/his actions and rationalizes her/his actions. When the narration is recorded in any conventional system, however, much of this aspect of the performance is lost.

Thematic Concerns of Nigerian Tales of Orphans

Apart from a surface structure, Nigerian orphan tales have a deep underlying structure that points to what is considered meaningful in the society. They explore many themes that expose the inherent problems in the society, which may include poverty, oppression, injustice, fraud, discrimination, pride, lonesomeness, jealousy, distrust, scapegoating, marginalization of a minority group, pretence, and so on. On the other hand the narratives teach the desired virtue of patience, sincerity, commitment, loyalty, vision, industry, self-reliance, magnanimity, bravery, obedience, faith, supernatural presence and so on. Thus, the orphan manifests as a poor wretch, an extraordinary human being, a scapegoat, a hard worker, a warrior, and so on. Essentially, the girl/boy who is an orphan starts life in the jungle or the suburbs usually after the death of parents. She/he is exploited in many ways until providence comes to her/his rescue.

In The Orphan and the Water Devils, for example, there is a surface theme of an orphan who goes in search of water for the village. The underlying structure points to the evils of scapegoating, injustice and discrimination. In The Orphan and the Old Woman, there is a surface theme of an orphan’s quest for a wife. Existing side by side is an underlying structure that has the themes of determination, vision, industry and charity. The evil of fraud, pretence and discrimination also pervade the narratives. Thus, the thematic concern of Nigerian folktales are numerous and comprehensive. Virtually all areas of life are touched. These include the spiritual, the moral, the psychological, the economical, and the sociological and so on.

Analysis

The multi-dimensional and aesthetic approach to the analysis of performance folktales would involve an understanding of the surface linear and sequential movement as well as the underlying images that constitute the conceptual element of any narrative. The study shows the aesthetic relationship between the synchronic and diachronic categories, that is, the structural models and categories. These comprise a look at the social context of the oral narratives as well as the individual creative elements the narrator use to make the work unique.

The Orphan and the Water Devils

The surface structure is the quest for water. There is scarcity of water in village. The underlying structure points to the fact that scapegoating, injustice, irrationality, discrimination and conspiracy are bad. The performance is divisible into three parts. The first part has three image sets or sets of activities. The source of crisis is scarcity of water.

1st, the village meets to address the problem of water.

2nd, the villagers conspire and send the orphan to the land of no return, the river filled with evil spirits.

3rd, the orphan sings to reflect his pitiable state in life.

In the second part, there are five image sets.

1st, the orphan arrives the river singing. The subtle tone here is the orphan’s need for sympathy.

2nd, the water devils lay ambush and arrest the orphan for interrogation.

3rd, the water devils bathe the orphan clean.

4th, the orphan narrates his ordeal in the society.

5th, the water devils help the orphan fetch water and instruct him to tell the villagers that the river is safe.

In the third part, the surface structure is the villagers search for water. There is an underlying structure of punishment for the wicked and supernatural assistance for the hapless and helpless. There are four image sets or sets of activities.

1st, the orphan arrives home, with the surprising tale of safety.

2nd, the villagers go to the stream.

3rd, the orphan and weak ones stay home.

4th, the devils arrest and kill villagers.

In the concluding set, the orphan reigns as king, with regular water supply.

The initial problem stated at the beginning is resolved in the encounter of the orphan and the villagers with the water devils. The images centre round contrasts between "poverty/wealth", "lonesomeness/companionship", "happiness/sorrow", "life/death", "clean/unclean", "reality/deceits", "reward/punishment", and so on. This oscillation of opposites provides dramatic twists that histrionically enrich the whole performance.

The orphan’s journey to the river is a process of cleansing himself and the society. The death of the villagers is their odyssey. Their encounter with the water devils serves to give them a taste of the dreadful and bitter experience the orphan had been subjected to by their lack of consideration and love. The orphan emerges from the narrative as a symbol of obedience, endurance and success in life.

The Orphan and the Old Woman

The surface structure is an orphan’s search for a wife. The underlying theme is that fraud pretence, discrimination and pride are bad, while industry, vision, determination, charity and hospitality are good. The narrative is divisible into three parts. The first part has six image sets or sets of activities.

First, there is the need for family care for the orphan, his father and an old auntie. This forms the surface structure of the first part. The image sets, when expanded look like:

1st, orphan’s father cares for old woman

2nd, orphan loses mother.

3rd, orphan and father live with the old woman.

4th, orphan loses father.

5th, orphan and old woman care for each other.

6th, orphan looks for a wife.

In the second part, the main object is the marriage of the Oba’s daughter. There are nine image sets or sets of activities which are expandable thus:

1st, there is an advertisement for the marriage of the Oba’s daughter.

2nd, the orphan goes to the Oba for a wife.

3rd, the orphan clears the stinking toilet.

4th, the orphan washes clean.

5th, Efe’s (Richman’s) son plays tricks.

6th, Oba and daughter give in.

7th, Efe’s son takes wife away.

8th, the orphan demands for wife, after hard labour.

9th, the Oba sends him away empty.

In the third part, the surface structure is the orphan’s revenge.

There is an underlying structure that points to the subtle theme of death and destruction waiting for liars and swindlers. There are six images sets:

1st, the orphan weeps over the injustice.

2nd, the old woman consoles the orphan and gives him some magical materials.

3rd, the orphan holds the village to ransom.

4th, people send gifts to the home of old woman

5th, the orphan restores people’s parts

6th, the orphan leaves the girl and Efe’s son to die in the river.

In the concluding part, the orphan becomes very rich ever after. He has very many wives and children. The image centres on oppositions between "life/death", "lonesomeness/company", "husband/wife", "poverty/riches", "filth/cleanliness", "lie/truth", "demand/supply", "justice/injustice", "magic/reality", "sorrow/joy", "revenge/forgiveness", "loss/gain", and so on. Gesticulations and idiophones are used for emphasis and descriptions.

A further consideration of the structure of the narrative reveals facts of various orders. These are geographical, economical, sociological and cosmological. Considering the geographical aspect, the place is a rural forest area where the people are engaged in crop growing as well as fishing. Economically, the people are traders of farm produce.

Sociologically, there is an established society of a ruler (Oba), his chiefs and other subjects who are either good or bad people. Some people are wicked and heartless. There are old people as well as youths. There is inequality, as some people wallow in abject poverty, while others swim in much wealth.

Cosmologically, there is much belief in magic and the supernatural. The latter intervenes in the life of individuals to ameliorate their odyssey during which they learn the need to be fair to everybody and get cleansed from their sins. The orphan gets cleansed from the evil of poverty and want. The orphan manifests as a symbol of patience, industry and strength. The fraudulent boy and girl emerge as symbols of cunningness and wickedness. Moreover, the orphan shows sign of supernatural talent for transformations.

The works show that Nigerian folktales about the orphan are interrelated and highly literary. They are replete with symbols and very interesting stylistic devices. These include the artists’ gesticulations and mannerism, music and dance, songs, language, figures of speech, idiophones, proverbs, repetition, rhythm, tone and so on.

The two tales are interrelated. They centre round the orphan. The orphan keeps on occurring in them and, as such, qualifies as a motif in the Nigerian narratives where it occurs. Moreover, the orphan has some very striking characteristics. The orphan personifies pain, suffering, lonesomeness, and extra hard work. The Nigerian orphan is parallel to the prototype:

Sex:Female/Male

Family Status: Double family, No parents,(Remarried parent) at all

Appearance: Pretty girl/boy

Sentimental/Status: People hate her/him

Transformation: Luxuriously clothed with supernatural help.

The Nigerian narratives of the orphan are interrelated in that they are often tales, about a heroine/hero, who is always in quest of some vital commodities required for existence by human beings. She/he seeks to acquire these commodities either for herself/himself or for another person, but in most cases for her/his/ entire community. The major objects of the quests are essentially food, water, wife and supernatural remedies and puzzles. Some helpful creatures always come to the rescue of the protagonist. Moreover, the supernatural assists the orphan greatly. The relationship between the heroine/hero in the various narratives remain constant: they are respectively involved with the royalty as envied rivals; with individual families as house helps or with the community as scapegoats, and in most encounters with other people not much value is placed on her/his life. Her/his chances of staying alive are marginalized.

The orphan is usually assigned some humanly impossible tasks. Miraculous supernatural machinations help protecther/him. Even death or his agents succumbs to this unique character. The orphan is constantly in contest with the royalty, the rich, the boastful, evil spirits or agents of death and so on. The orphan in the eight performance narratives analysed above appears immune against the whims and caprices of ordinary human beings and even evil spirits because of her/his peculiar origin and background, which leaves her/him almost entirely to the care of nature. She/he survives on both human and inhuman food to grow up and this appears to give her/him immunity against very many things.

Narrative and Stylistic Devices

In The Orphan and the Water-Devils, songs are used as a narrative device to move the tale forward and dictate its tone. The songs evoke the spirits of the river and the forces to have pity on the orphan and allow him pass safely. The orphan cries to God about his piteous states in life and weeps without consolation. The opening formula is idiophonic and appealing: "Okhame gbudu Okhame nyakan." It suggests the sound of something really great and overwhelming. Other idiophones include, "tipu!" "se se se" "riririri," "fiekpia," and so on. "Se se se"suggests the sound of something completely and thoroughly washed.

"Ri ri ri ri," suggests the sound of a long row of people moving in an unbroken chain with frenzy and enthusiasm. "Fiekpai!" suggests the sound of a rubber bag filled with water. The closing formula is appealing. "That is how far my story goes. It will not pain my hand, it will not pain my leg." The language is simple and close to the everyday language of the Esan people.

In The Orphan and the Old Woman the narrator arrests attention by the use of suspense. People watch out to see if the Oba would really give out his daughter to a very poor orphan. The orphan is deprived of the wife, despite his industry at clearing out the stinking toilet. The audience becomes eager to know what the orphan would do next. The orphan gets out a small gourd from his late father’s dilapidated house and the audience is full of suspense to know what happens next, that is, what use the orphan would make of the small gourd. The audience also wonders what the orphan would use the magic stick to do. The idiophone, "Yo– o– o- s" fills the later part of the tale. It is used to suggest the sound of an element cooling off. The language appeals in its simplicity. For example, "come and die! You think an orphan can go where real human beings go. He is bringing himself out, instead of him to hide." "Yo – o- o- s!"

With the foregoing analysis, answers to the questions asked earlier in this paper could be stated thus: that tales are common with the Esan people or tribe of Nigeria; that through the instrumentality of folktale performance, the Esan community as a microcosm of the multi-lingual and multi-religious nation of Nigeria projects some of the travails they have faced as a people; and, that all along in this people’s history and culture, they have confronted and contended with the issue of orphans. This is probably why they fantasize in their tales what is unique about the orphan in the society. Hence, the narratives could be seen and approached as highly imaginative tales for learning about the totality of life of the Esan people, their culture and their idea of what is truly beautiful.

It is also evident that right from the past the orphan has been discriminated against and marginalized, many have perished due to lack of care. However, a great majority who stick out their necks to weather the storms and succeed in life have achieved their aims marvellously. There is a significant difference between the life of the orphan and other persons. Some people regard the orphan as an ill-fated child, a bringer of bad luck and treat her/him with scorn at the slightest opportunity. However, some people who have gone out of their way to help the orphan get the reward. The orphan in Esan folktale reciprocates, as much as possible, any favour done her/him and remains very loyal in any relationship. The orphan is generally very industrious, self-reliant and generous. She/he is, in most cases, very determined and has a clear vision of life, so she/he applies herself/himself fully to any assignment she/he is involved in.

God (The Supernatural) sustains the orphan and fortifies her/him against all mishap. He provides for the orphan greatly. The orphan’s personality transcends all ages. The problem of the orphan is still with the present generation. Many orphanage homes abound, where orphans are given refuge and prepared for real life in the society. However, some people still exploit the orphan and use her/him as house help who does almost all the domestic work in the household and yet receives little or no food and very minimal consideration in terms of clothing and freedom to enjoy life. In some places, the orphan does not go to school nor do what other privileged children do. The orphan is psychologically down most times and requires much encouragement and kindness. The orphan needs to be fully appreciated because although her/his background is poor she/he evinces qualities any community tries to encourage in the subjects, such as loyalty, kindness, patience and hard work. She/he shows that no man should be despised because she/he is poor. People should be given the opportunity to prove their worth and be appreciated on their own merit.

Other lessons in the study include the fact that the stories are highly imaginative and emotional. They successfully demonstrate the fact that Nigerian folktales are really highly developed work of art and language with various levels of meaning signified by images and symbols. The characters and events are contrasted. They essentially signify the meaning of the tales. Good performance of the tales signifies the aesthetic thirst of the audience.

The orphan needs help. People and government should, therefore show much kindness to the orphan. Deliberate programmes should be mapped out to make people aware of the plight of the orphan; get the orphan properly rehabilitated and integrated into the society. More assistance should be given to orphanage homes, and more of them should be established and the services should be free or highly subsidized to improve the lot of the orphan.

At the societal level, parents should make every effort to live well and live long, in order to care for their children by themselves. It is believed in the traditional society that disobedience to some natural laws causes the untimely death of some parents.

The orphan is usually psychologically lonesome. Adequate counselling would give her/him the presence of mind she/he requires to lead normal life.

The aesthetics of the narratives should be identified and relished. For example, the gesticulations, the idiophones and the numerous songs that dictate the mood and tempo of the narratives should be enjoyed. Whatever is considered beautiful in the narratives, that is, in the folktale performance culture should be emphasised.

Narratives involving the orphan would make good reading in the literature curriculum of all schools in the Nigeria and elsewhere, following the recommendations of the committee implementers of the Universal Basic Education (UBE) system of education. The narratives in the appendix are highly recommended for any literature class.

The study also shows that the experience of the orphan in Nigeria is not different from that of her/his counterpart in other parts of the world. The orphan lacks adequate care and is marginalized. Concerted effort should be made to improve her/his lot at the global arena. Adequate lessons should be drawn from the experience of the orphan in Nigerian folktales.

- Aluede,C.O. (2006). Esan Native Doctor’s Musical Instruments as Spirits: Basis and Relevance in Contemporary Nigeria. Iroro: A Journal of Arts, 11(1&2): 338-344.

- Obuke, O. (1977). Analysis of African Oral Narratives: The Marxist Approach: A Paper Presented at the Workshop on Radical Perspectives on African Literature, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, 1977.

- Egharevba, J.U. (2005). A Short History of Benin. 5th ed. Benin City: Fortune and Temperance Publishing Company.

- Ewanlen, T.A. (2011). The Greatness of Esan People. Ekpoma: Ewanlen Image Production.

- Eweka, E.B. (1992). Evolution of Benin Chieftaincy Titles. Benin City: University of Benin Press.

- Federal Republic of Nigeria Official Gazette, No2, Vol. 96. (2009). The 2006 Final Census Results. Abuja: The Federal Government Printer.

- Okojie, C.G. (1994). Ethnographic Studies of Esan People. Benin City: Ilupeju Press.

- Peirce, C. S. Collected Papers (8 vols), Eds. Charles Hartshorne, Paul Weiss and Arthur W. Burks.

- Cambridge Mass: Harvard UP. 1931 – 58. Vol. 2, para. 228.

Esan Folktales

THE ORPHAN AND THE WATER DEVILS

Once upon a time there was scarcity of food and water. The oldest member of the community summoned a meeting of all the members of the community to find a solution to the problem. The people could no longer fetch water from the river because the dreaded devil, ‘ojiugbelimi’ and his men took over the river. Any mortal who went into the river was killed.

It dawned on the community to use the orphan in their midst as a sacrifice to the devils. They resolved to send him alone to the river to fetch water for the community. The orphan had no option, so he had to go. He rationalized that his death in the river would send him to join his parents in the other world and enjoy their love. He was given a very big calabash to carry. As he went along, he sang:

"Whosoever is in the bush, face your own business, my father is dead and buried,

My mother is dead and buried, that is why the unkind people are sending me to the river, with such a big Calabash, because I am an orphan"

He sang and wept without consolation. He cried to God about his piteous state in life. He sang so much that the dreaded devils jumped into the bush and he passed, without obstacles, to the river.

He reached the river and started fetching water, then, the water devils appeared and surrounded him. They got hold of him and washed him very clean with their type of soap and cosmetics "sesesesese". They interrogated him and he narrated to them his ordeal in life because he had lost his parents. They consoled him. They sympathized with him and helped him fill his Calabash with water. They put it on his head and instructed him to go home and not mention anything about them. In short, he was to say to water devils were non-existent. The orphan expressed his profound gratitude to these spirits and went home very fast.

He went home and found the people waiting for him. He put down the Calabash and people drank. In short, some impatient people dragged the Calabash down from his head. The Calabash fell and got broken and people rushed around to have just a drop of water on their patched lips and tongues. They asked him how he was able to survive the journey. He informed them that he went to the river undisturbed and that there were no devils or obstacles on the way. He told them he got to the river, had his bath, fetch his water and came home smoothly.

The people, on hearing this, became very happy. They all prepared for the river and left behind only the orphan, the aged and little children. The orphan was told that he must not go to the river again, since he had gone before, but that he should stay at home and look after the younger ones.

All the villagers then trooped to the river, "ririririri!" carrying very many calabashes. Some people, carried as many as three calabashes at a time. When the dreaded devils heard them coming with all the noise, they dashed into the bush and allowed all of them jump the river, ‘tipu!’ they all rejoiced very much at the sight of much fresh water. They drank until their bellies protruded and became round like water pot, "fiekpia!" at the peak of their drinking and rejoicing the water devils appeared and rounded them all up. They killed all of them.

The orphan and the people at home waited in vain for the people to return. When they failed to return the orphan concluded that they must have been killed by the water devils.

The village was then left with the orphan and the people he was to look after. From this crop of people emerged a new race under the rulership of the orphan. By this singular act of the orphan becoming king the water devils no longer disturbed the people in the river. They had safe and abundant water supply.

There was once an old widow. Her brother cared for her and sent her the best yams in his farm. After some time, the brother’s wife died, so the brother brought her into his house to live with him and his only son. Not long after that, the man died so the only son, now orphan lived with the old woman, Odede and they both started taking care of each other. The orphan farmed for the old woman. He fetched her firewood and water and made sure her pipe was always filled with the best tobacco. The old woman loved the orphan and cared for him like her own son. The old widow lavished all her love on the orphan, for she had no child of her own. Whenever she remembered the kindness of the orphan’s father, she determined to see him grow to real manhood, so as to perpetuate the late father’s name.

One day, the orphan came home grieving that his mate had wives married for them by their fathers, but he himself had remained single because he had no father to marry a wife for him. The old woman told him to forget all about marrying like his mates and told him, "An orphan does not do what other people do."

One day the orphan came home and told the old woman that there was an advertisement for the marriage of the Oba’s daughter. He told her that what was required was not money, but that he who was able to clear the Oba’s seven years old pit latrine and line it with fresh wood would be given the Oba’s only daughter to marry. He further informed her that all young men were reluctant to do the task that was why the girl had remained unmarried. He expressed his wish to go and do the work and bring back home the coveted bride. The old woman told him to forget about the whole plan because whether he worked hard or not, whether he cleared all the toilets in the world nobody would give him, a poor orphan, the Oba’s daughter to marry. An orphan, she repeated, did not do what other people did.

The orphan remained adamant. He went to the palace to inquire about the advertisement and the palace warden told him it was true all he needed was to clear the toilet and reline it and the new wife would be his own. The orphan agreed he would do the work and asked to be shown into the presence of the Oba.

The Oba asked him in. he told the Oba that he was ready to do the work and marry his daughter. The Oba looked at him a second time, with his eyelids lowered as if to ascertain whether the youth was in his right mind. He then gave him the go ahead and the orphan attacked the work with much vigour. The thought of marrying the princess propelled him on and he worked very hard at the otherwise stinking and arduous task. All passers-by closed their mouths and nostrils and wondered who was polluting the environment so. They wondered whether a human being was really clearing the toilet. The orphan did not mind their derogatory comments. He knew his target pretty, royal bride, so he struggled on. He stripped and had on just underpants.

At last, he accomplished the task and told the palace warden to tell the Oba’s daughter to give him some water to wash himself clean. The girl put some water in a disused piece of broken calabash and placed it near the bush at the backyard. The orphan went thereto wash down. The news of the feat he had just accomplished swept through the whole town like wildfire.

Meanwhile, the rich man Efe’s son, who had earlier refused to do the work went to the work sight to see things for himself. He really saw that the orphan had done the work and so was the rightful owner of the new bride, the Oba’s daughter. He quickly thought of what to do to have the wife to himself. Efe’s son rubbed red mud from the pit toilet the orphan dug all over his body and went to the Oba to ask for the daughter in marriage. He saluted,

"Zaiki, (your royal highness) I have cleared the toilet, so I have come to take home the new wife. You could ask the palace warden about the extent of the work done."

The Oba then called his daughter and instructed her to follow Efe’s son, since he had accomplished the task. The girl knew the truth of the matter, yet, because she had secretly wished she had married Efe’s son and not the poor orphan, just asked the father,

"My father did you really say I could follow Efe’s son home?"

The father replied, "yes, he had cleared the smelly pit toilet." The girl pretending replied, "since it is your wish I cannot disobey you, I will follow him." So Efe’s son took the wife home amidst great rejoicing. People commented that the rich man’s son and the Oba’s daughter were really a good match.

Meanwhile, the orphan finished bathing, dressed up and went to the Oba and salute,

"Zaiki, I have cleared the pit toilet very well. I have lined it with fresh wood, so it is now brand new. The palace warden can actually tell you exactly what happened. So please, give me my wife, the Oba compensation of my hard work."

The Oba lowered his eyelids and looked at the orphan a second time and said,

"Run away from here, you madman. The person who did the work has gone away with his bride. How can you be so clean and well dressed and you claim you have just cleared a smelly seven-year-old toilet and dug a new one. Run away from here before I get you arrested for telling lies. You impostor!"

The orphan pleaded that the Oba should inquire from the palace warden and even the girl, herself because they both saw him doing the work. Yet, the Oba got him chased out of the palace. The orphan wept home. He remembered the old woman’s saying,

"No body will give you the Oba’s daughter, whether you worked or not. An orphan does not do what other people do."

When he got home, the old woman welcomed him and asked him about the new bride the Oba had promised him. He wept and told the old woman,

"He did not give me …" and wept very painfully. He refused to eat any food for days.

On the third day the old woman said,

"Enough is enough! Get up, wash yourself and eat. You have cared for me more than any son would care for his mother, despite the fact that you are not my son. Now, I will do for you what a mother would do for a good son." She continued, now determined to revenge for the orphan:

"Your father alone could cause harmattan in this part of the world, when he was alive, now go and search his room and get one little gourd you will find hanging there."

The orphan went into his father’s dilapidated hut and really found the object hanging on the wall and brought it to the old woman. The old woman then instructed him to blow the content into all directions in the town. The boy did that and there was great harmattan wind in the town. All wells in the town including the Oba’s well dried up. Only the river became the source of water and everybody started going there. The old woman then gave the orphan a very tiny stick to place on the stream road and he did so. From then on, anybody who went to the stream lost his or her reproductive organ. The orphan fell out and ran into the river "kpekpekpe!" The people were then stranded. Then followed the Oba’s daughter and Efe’s son. They went in the euphoria of their connubial felicity. They were also trapped. They begged the people around to help them get hold of their organs, as they ran ahead of them into the river and the people laughed and told them that they also had a similar problem. Next, Efe, himself went to the river and was also trapped. Then, the Oba and his wife decided to go to the river and see why people who had gone to the river for over twelve hours would not return. As they crossed the stick, their organs fell out, too, and ran into the river. The whole town was thus trapped in the river. Some people there really commented on the injustice done to the orphan.

Finally, the old woman told the orphan, himself to go the river. She instructed him to pick up the stick as soon as he got there and say,

"Y-o-o s!" and touch anybody he wanted to help with the stick and his or her organ could be restored. So he went.

As soon as he approached, some people started making derogatory statements about him. Some said,

"Come and die! You think an orphan can go where real human beings go. He is bringing out himself, instead of him to hide. Unlucky being. A fool!"

However, some sympathized with him on his loss of the bride he actually sweated for. The orphan heard all the comments as he reached the stick; his own phallus fell out and ran a bit forward. He quickly picked the magic stick and touched his body and said,

"Y-o-o s!"

Immediately, his own organ was restored. Everybody was astonished and begged him to help them. He then struck a bargain with them, that all of them, on getting home would send half of everything they had to the old woman for keeps. The people promised they would do much more for him. He then started to restore their parts one after the other, filling the air with the sound of,

"Y-o-o s! Y-o-o s! Y-o-o s! Y-o-o s! Y-o-o s! Y-o-o s!"

He progressed fast in the task of restoring the fallen organs until it remained the rich man’s son, the Oba’s daughter, Efe, himself and the oba, and spoke thus:

"Listen you, Oba’s daughter, you are very wicked. You were most unfair to me. You knew in your heart of hearts that I cleared your father’s toilet and so, I am your rightful husband, yet you followed Efe’s son because he is rich. You, Efe’s son, you are a thief. You knew you did not work. You just rubbed on the red mud I dug out and you went to show yourself to the Oba and claimed my wife, so the two of you remain in the river. You Efe, you know very well that your son did not clear the toilet, yet when he brought the wife home you celebrated lavishly. I should have left you to suffer. However, I will let you go. "Y-o-o-s!" and Efe’s part was restored. He worked up to the Oba and said,

"You are a very partial king. I did the work and I told you so. You chased me out, instead of investigating to know the truth. You deserve no pity. However, because you the Oba and the Oba is always right, go your way, Y-o-o-s!" and the Oba’s part was restored. Everybody was astonished beyond words. They all ran home to fulfil their promises. They all took one out of every two things they possessed, including daughters, sons, money, foodstuff, clothes, and jewellery and so on, to the orphan’s house. The orphan, thus, had very many wives, slaves, money and all items required for abundant life. He became the wealthiest man in the neighbourhood and the news about everything that happened spread like wild fire. The old woman later died and the orphan gave her a befitting burial.