Before discussing about 'Tribal Art’ it is necessary to define the tribe. In our general perception we understand that a tribe is a primitive community inhabiting a particular locality or region. Leaving other aspects of this primitivism, when we are dealing with the art presentations, it is better to have an idea of the existence of art in tile archaic society. As all art are the representations of emotional or otherwise attempted interactions of man in his environment, it is no exception that a primitive tribe, or tribes in broader sense, when region like Orissa is to be taken into consideration, give vent to the same, through the medium of colour or drawings. The drawing at times and more often takes form of engravings whatever be the medium is. On this backdrop the aim of this paper is to find out the probable roots of tribal art and its continuity. The continuity stems from modern relevance or fascination for the same.

Orissa is domineeringly a tribal inhabited region. The tribes dwelling in it though sixty-two in number, yet a dozen or so dominate the scene n respect of their numerical strength and distinctiveness of cultural patterns. In order to find out the primitive character in their cultural presentations in art we are to study the manifestations of their art in various spheres, such as, religion, social activity, belief, etc. The primitiveness is vividly expressed in the religious actions of a tribe since supernatural awe guards against its alteration.

The tribal religious art in Orissa, therefore, might have less chance of its being diluted. But religious art forms are not indigenous to the tribes since their inception. These are modulated through super positions of several cross currents on the original culture. The evidences of these art forms are difficult to be attested in the absence of comparative levels existing till to this date. Naturally, we have no other alternative but to look for the same in the prehistoric art forms, though, demographic contours and waves are difficult to be determined as constants. Coming to the religion of the Orissan tribes, again we find diversities in their expression pertaining to regions. Inspite of the same, basic under current of general nature persists on which a broader assessment can be made.

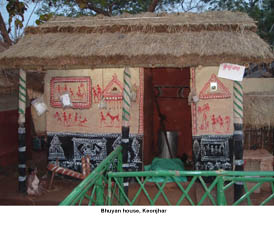

In the religion of the tribes, ancestor worship and ceremonies constitute a major factor. Beginning from the death till the commemoration ceremonies through the mortuary rites the tribal mind is either sympathetic or apathetic to the soul of the dead. The dead, to many of the Orissan tribes, dwell in the Under World as human beings do ill their present life. They require facilities and in turn expect their relations in this world to provide the same for them. The Saora ittals (picture painted on walls) are connected with the spirit of the dead. If wall paintings are to be searched for in the earliest period we find prehistoric paintings on the rock house at Khariar is closer to Saora region. Resemblances in the style between the Saora and the prehistoric Yogimath wall paintings exist to some extent. For instance, the Saora wall paintings are found mostly modeled inside a house denoted by rectangle, square or a circular frame drawn on the background of red painted black wall in white. May be the Yogimath painting considered to be drawn on the rock surface, which is, but a rectangle house in frame. The same is also to be found in the wall or door paintings in rural Orissa, particularly in the districts of Puri and Ganjam. Chitalagi Amavasya is the occasion of their presentation; yet the reason and the aim of these drawings or pictures are different in space and time. The Oraon painting of elephant, & drawings on the wall in white, red and black are intended to decorate the walls as well as to ward off the evil eye. The black wavy circular lines circumscribing diamond patterns are drawn. Fine elephant figures are also seen drawn on the walls (Roy: 1915, 132).

|

The Saora paintings on the walls have designs and symbols (Elwen: 1951: 205, 213, 211) which could be found symmetrically occurring in the Harappan and the prehistoric paintings of Middle India. The triangles, lozenges, chevrons, loops, rows of hatching, parallel lines, floral presentation, line of dots, wavy lines, etc. remind us of the designs depicted in the painted pottery from Iran to that of the Indus culture (Fairservis, Jr.: 1971: 164, 206, 290). Even the human Figures and the conventionalized human figures shown in the Harappan seals and paintings have echoes in the Saora paintings. When we examine the patterns shown in the traditional modern clothes prepared in Sambalpur, Nuapatna. Berhampur we also come across similar designs in an altered condition. The floral designs, and styles on these Saora paintings also reflect that of the Malwa, Jhukar, Kuli and Harappa culture’s (Allchins: 1968, Fairservis, Jr.: 1971: 22). Even modern fabrics are imitating these designs which are much in public demand.

|

|

The Meria sacrifice of the Kondhs is a religious belief, which has boon thriving from a long period till the English suppressed it. The victim was offered to the Earth Goddess for good harvest and bringing good fortune to the Kondhs. The different clans of the Kondhs tribe have been performing it. The posts meant for the victim are sacred to all and the designs engraved on them though vary from clan to clan yet resemble old patterns which are found in the chalcolithic and Harappan design impresses on the pottery types. The alternate hatchlings, rows of triangles, diamonds, etc. adorn those posts. Though far removed from the point of space and time yet these patterns have survived till this date. We find similar patterns in Saora, Gadaba and Kutia Kondh textiles though in recent years infiltration of modern designs are making some impact on them. The tribal patterns have also infiltrated to the folk textiles of Orissa evidenced in Maniabandi and similar textile patterns, which have much demand at the present market along with the colour of the clothes. The wide red borders in the Saora cloth was a household pattern appreciated by the folk in the coastal areas of Orissa. The Berhampuri textiles are also good examples of this though the colour changes.

Also related to the Meria sacrifices are the masks. Elwin has depicted gourd masks used by the Kondhs as substitutes for human skulls in the sacrifices following the suppression of this religious observance (Elwin: 1951: 144). The red and white beads are arranged to appear as eyes, nose, teeth and ears. But these masks are rather a development of the art to depict demons or mother goddesses, which could be used instead of human skulls since their availability became scarce. On the other hand Bhuinya mask from Bonai (Elwin: 1951: 141) has resemblance with a stone head design from Kandahar in Afghanistani (Fairservice, Jr.: 9171:133). If the preparation of heads whether mask or stone was the intention and a similar code affect their fashioning then a common cultural current might be the source of their emergence leaving aside the distance and time period affecting them. Masks prepared by Pabs in Sundargarh area to be used in their dances in honour of their ancestors can also be taken as religious in nature. The modern masks prepared by folks, particularly the folk-dancers could be easily identified as survivals of the old customs along with the admixture of modern notions. The Chhau and opera masks as well as the mask used in epic performances by the folks are vivid examples of survival, continuity in an altered situation and modernization of archaic culture. These might well have influenced the Koya or Gond hero-posts with human heads carved and planted on the grave of the deceased. The same anthropomorphic designs are at the root and their continuity is the cultural survivals.

The peacocks fashioned on wood, metal or at rare instances burnt earth decorate memorial pillars in the Gond, Kondh and Saora communities. However, the Saora Sadru-shrines in their villages and the top of ittal depiction as well contain peacock figures, which are considered as the guardian figures of the shrines. The pattern of various peacock figures found on them has echoes in the Mohenjodaro and Harappan depictions on the potteries. Particularly the pottery of cemetery-H culture (Sankalia : 1974 : 394) of the Harappan civilization have various peacock and other figures. Not only that the neolithic-chalcolithic cultures unearthed from the Iranian-Afghan border lands to the Gujrat, M.P. and the Ganga valley also yields similar depictions in the potteries. Thus the root of this culture is to be found existing from very ancient times. Evidence of the same is also available from Chanhu-daro (Fairservis: 1971: 22). The continuity or rather modern relevance is not hard to seek. The horn works wooden works and many feather works are prepared with peacock motifs and a beautiful specimen of horn work from Parlakhemundi is found preserved in the Orissa State Museum. The paintings prepared in the present time have not given up these symbols. The declaration of the peacock by the Government of India, as a national bird has stepped up paintings of their figures in various patterns.

The cult of Bhimul though linked with the religious performances of the tribals has its origin from the story of the Mahabharata. But it is not certainly known when it got into the tribal world. Elwin has given some account of the cult and has shown how it has become the symbol of various tribal beliefs and religious practices. But it is quite certain that the cult is not matured in Orissa and the Kondh paintings in honour of this god vary from anthropomorphic to that of uncertain symbols. The symbol paintings seem to be mature than the other forms. However, these paintings and woodcarvings in respect of these are a meaningless lot of designs and their roots are hard to be traced though not the cult. Archaeologically the Mahabharat period goes back to about 1200 BC but their infiltration to the tribal area might have been during the Mohammedan rule in India when large-scale migrations occurred into the tribal and regional areas. The tattoo marks impressed on the faces of the Kondh girls in honour of Bhimul might have their roots in the chalcolithic cultures of the sub-continent. The art on the faces consist of triangles, dots, parallel lines, etc. The popularity of Mahabharat episodes in Cinema and TV serials though uphold the cult in its modern settings yet the pattern remains to be adopted in the crafts.

A cult of the Sahibasum which grew among the Sattras in Orissa for which sacrifices made, images carved and placed in the way sides of the Saora land is of recent origin. The cult originated in the British rule. They are represented by anthropomorphic figures of various dimensions. These figures are carved crudely and meant for caricatures of outsiders particularly visiting officers and foreigners in Saora land. The modern relevance of this is only to express the disgust of the tribes to the outsiders who are never innocent in their intentions. It can symbolically be used in modern art form.

The tribal art of Orissa as reflected in various forms of decorations, the media being varied, only a few of note can be depicted as instances of the same. These include tobacco containers, combs, ornaments, musical instruments, woodcarvings, headdresses, etc. The motifs on the tobacco pouches have been elaborately carved Kuttia Kondh decorations on the bamboo containers of tobacco are mostly diamond or lozenze patterns prepared by various methods. Through intersecting diagonal parallel lines these are beautifully and elaborately prepared. To make these diamond designs prominent horizontal parallel lines are drawn to fill in the spaces in between these diamonds. Opposing wavy lines either perpendicularly or horizontally on these containers creates Rows of diamonds. Parallel wavy lines intervened by straight parallel lines are also found to be decorating these cylindrical pouches. There are also breaking up of parallel lines in between sigmas and diamonds to indicate a refrain from the continuity of these chains or lines. These designs could as well be applied to the walking sticks to make beautiful pieces as is done in Africa (Bohannan: 61: 90)

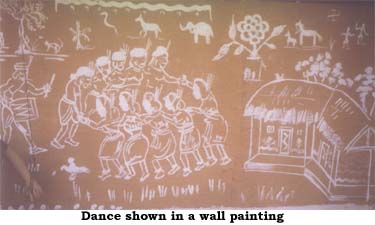

The decoration of the body is another aspect of tribal attempt to beautify a person. The Kuttia Kondhs decorates their bodies in ceremonial dances. These are line drawings in red and white. The designs made are in square and parallel lines (Elwin: 1951: 16). The other aspect of body decoration whether religious, ceremonial or sportive is the tattooing of the face and body. The designs being depicted are dots, dashes, triangles, circles and floral patterns. At times faunal presentations are to be met with. Kondh, Saora, Gond and such other tribes elaborately decorate their body with tattoo marks. In the recent past it was also a practice among the folk communities of Orissa during Danda Nata festival. But their relevance is sharply fading out. The decoration of the body in colour is a worldwide phenomenon starting from Africa to that of the Southeast Asian countries and Australia. Though it is fading out yet the designs could well be utilized by textile or other industries as well as cottage industries for finished products.

|

The decorations are also found on the combs. These are most interesting and striking. The combs have artistically presentations in their carvings. The makes and designs of the Juang combs, both male and female, are beautifully prepared. The gents comb of the Juangs reflects close replicas of modern make. In spite of the same tribal hafting process and the bamboo medium single these objects out from the modern ones and compels one to think that the modern designs probably have been copied from their tribal existence. The depictions in these combs are lines drawn either parallel or horizontal on bamboo or wood. The patterns are usually dancing human and animal figures. The dancing animal figures are well carved to produce the effect. The peculiarity in the Juang combs lie in their drawing of human figures. Symbolic human beings and alternate hatching patterns are also found accompanied by animals, such as elephant, horse; circular and wavy zigzag lines surrounding them. Parallel lines are drawn in tit-bits to indicate the thickness as well as the body decoration of objects and men. Swastik marks, diamonds, parallel lines and denticulate wavy lines oriented inside and outside the human outlines mark the specialty of these combs. Even such wavy lines are set to mark the mouth of a horse in a Juang comb. |

A diamond design flanked by diffusing straight lines makes the left eye of this animal. It is set on a handle of the gent's comb. The human faces usually left blank but wavy denticulate lines circumscribe their circular heads. The body is surrounded by such lines and the inside of the body is decorated with netted cross-lines. The insides of some of the human figures are decorated with parallel perpendicular lines with refrains in between the top and bottom rows. The horse riders are holding the reins of the horses shown in wavy denticulate lines also. Probably these decorated combs are intended to be presented to the sweethearts or to fix them on the head of maidens. Both the boys and belles might be using these combs for fixing them on the knots of their hair. The figures either human or animal could make ideal models for modern cartoon learners to depict suggestion - pictures. The curve and the suspending pendant designs are good examples for the decorators in reception pandals (Elwin: 1951:52-53; illustrations). The Kondh combs though taking the shape of artifacts of the neolithic period are presentations of general nature and artistic acumen is meager in their finish. Occasionally a braided knot is seen with the purpose of keeping the haft and the handle together. Yet the material of their hair-arranger is bamboo. The Saoras use wooden combs and the Gonds and Kondhs also prepare the same. Some of the graffiti marks carved on these combs have echoes in a copper axe head from Navdatoli (Sankalia: 1974; 462). It is found those wooden combs of rectangular, semi-circular and triangular types are used in the Kondh society.

The ceremonial and other festive dances demand head decorations. The headdresses are found peculiarly used since pretty ancient times. The Koyas, Kondhs and Gonds are known to have been using these headdresses. Particularly the bison horn and the peacock feathers are the objects, which adorn these dresses. At times, feathers of cocks and other forest birds decorate the same. This type of headdress has its roots in the chalcolithic, (Sankalia: 1974: 354) even earlier in the prehistoric context (Gordon: 1958:No. 11 of Fig. 12) There are also laced cowries hell decorations in these headdresses which are found to be adorning the Koya dancing head robes. A specimen of the same is played in the Tribal culture gallery of the Orissa State Museum. Elwin has depicted a Kondh turban capped by the beak of a great Hornbill (Elwin: 1951: 62). The head decorations of the women are simple and not burdened with beads or other types. The Koyas and Bondas use more of them. The Koya women wear brass silver, palm leaf fillets on their head. In most of the cases brass and silver fillets are decorated with lozenge, diamond and parallel line designs which are again found to be adorning the chalcolithic potteries. Bonda women also use coloured threads or circular fillets on their head. The headdresses could very well make specimens for opera parties to reorient them to suit their themes. In fact opera on Ramayana themes and Gopaleela or other such mythological subjects could very well find the relevance of these objects for their modem appliances. The Saoras, Dongaria Kondhs and Kuttia Kondhs use different types of hairpins with simple workmanship. Usually these pins are made with concentric circular patterns on umbrella designed hairpins having differently finished tops. So also their hair do differ from tribe to tribe. Even Kuttia Kondh youths are seen knotting their hair behind and decorating with chained silver hairpins. The designs on some hairpins indicate diamonds, parallel lines and dots.

The beads are the foremost of the women's decoration. In the tribal communities inhabiting the inaccessible areas away from the urbanized localities, the beads serve as their essential ornaments. These beads are found in terracotta, metal, shell and seeds of various trees. Besides, grass leaf, bark coloured in different hues are knitted or tagged to make excellent necklaces or head and ear ornaments. The Bonda women have retained these decorative types intact till this date. The colours of the beads are generally white, yellow, red, green and black. Juang women were having these beads tagged for use in different fashions. The beads can be utilized for the preparation of window and door drapes when wreathed together. Also they could make table covers and flower baskets, etc. Even they could make suitable substitutes for the costly jewelry.

The textile designs of the Saora, Gadaba, Bonda and Paraja are knitted in simple parallel lines. Even these lines are seen indicated in dots, herringbone, double dashes or hatching in miniature or prominent form.

|

The Lanjia Saora textile designs also indicate interesting types. The tailed clothe of male Lanjia Saoras includes a pattern of dashes and squares with central dots. The colours used are red, white and black, which are applied to the yarns and woven in rotation. The designs also include flying bird, diamond, arrowhead and alternate leaf patterns. Besides, small parallel lines are also woven. Other patterns on the reverse of these clothes are lines of crosses and small squares arranged differently in red. The squares designed in 3,2,1,2 and 3 pattern are arranged from top to bottom. At times this design is elaborated by a pair of squares lined at the top and bottom of the arranged pattern of squares. To indicate breaks of this pattern a single line either horizontal or perpendicular is woven. But at the tail end the pattern are seen as circles associated with a pair of parallel lines woven in 1:2:2:1 pattern in repetition. It results in bringing out the fourth numeral of the Oriya number. The typical Saora Sari designs include alternate squares in red and yellow arranged in lines. This may twice or once repeated at various points. Another pattern found in this sari is horizontal yellow dashes flanked below by thicker or wider red dashes. These patterns are to be seen in the textiles preserved in the Orissa State Museum. These designs could well be utilized by textile industries for cloths, screens etc. The Dongaria Kondhs prepare designs on the textiles with rows of triangles intervened by knitted dots. Parallel lines of hatching and alternate hatching is nicely done on the borders at both the ends. Alternate hatching provided with a border knits even triangles. The border of this cloth is also to be found provided with a row of triangles. A specimen of this cloth is displayed in the Orissa State Museum. These designs have found their way to the folk-art and depicted on the horse back coverings prepared by the folk-dancers. This design is also found in the chalcolithic and Harappan potteries. The modern applique works could very well utilize these designs to fetch inviting markets on competitive basis. |

|

The ornaments either used in the hand or the neck contain carvings. Koya bangles in the Malkangiri area are flat in shape and incised with circles. Another pattern in this ornament is the incision of close alternate strokes forming a snake pattern. Fish pattern in similar manner is also available in another such ornament. Even in anklets triangles are incised in the inner side, which are parallel lines of dots. These have been impressed beautifully. In certain anklets the faces have been modified into snake mouth design and the body decorated with angular wavy lines. The earrings are also seen with parallel lines incised in small perpendiculars and dots. In the silver neck ornament (Khgala) used by Bondas and Koyas alternate diagonal lines have been incised in cross pattern which have found echoes in the pottery designs of Harappan and post-Harappan periods (Lal: 1951:38-39; 1954-55:5-151). These pattern could easily be appreciated if cast in moulds and seals and applied to the woodcarvings as well.

Tribal art is more vivid in the woodcarvings and embrace varied aspects of tribal life. It includes hunting, depiction of animal and men, dancing models, etc. Kondh carvings of dance scenes on the door are more lively and moving. Such carvings are from Totaguda and Jantri in Koraput district (Elwin: 1951:133). Juang door carvings of dance from Baupal, Keonjhar (Elwin: 1951:133) and Saora modeling of a dance type on the door (Elwin: 1951; 131) have similarity in depiction. Steel dancing figures and musical instrument players are nicely carved on a musical

Instrument (Elwin: 1951:134). Door carvings of human figures imperfect in nature are found on Saora doors. Two opposing triangles and thick lines drawn for the limbs of a human being on a Saora door and a Venus figure depicted on a Juang door (Elwin: 1951:117) indicate workmanship of the tribal art. The Juang carving is more proportionate and artistic. Bhuinya carvings in wood, particularly the images of headman and his wife (Elwin: 1951:116) and on the central pillar of the boy’s dormitory (Elwin: 1951:114) are more symbolic than moving. However, the images of headman and his wife express pensive mood and in that respect near to perfection. A carving on the door of a Kuttia Kondh by a Pano at Rangparu in Ganjam district (Elwin: 1951:108) indicate multiple scenes in respect of animals. The faces of the bovine depicted in this carving have echoes in the mythic boar of prehistoric middle Indian rock art (Gordon: 1958). The other animals treated are fishes showing their bones, pangolin, dog, hen, cow with calf sucking milk, lizard, etc. The secular depictions include trees, bows with arrows, flowers and decorative designs. In the decorative design triangles, dots and straight lines forming angles are to be seen. The work does not indicate any systematic arrangement or symmetry. For instance, the dog is carved larger than the cow. Similarly Kuttia Kondh woodcarvings on the door (Elwin: 1951:101) also exhibit carved patterns of diamond, triangle, circle, square and line drawings. The outlines of human figures in some cases indicate borders in angular wavy lines. The Saora woodcarvings of elephant on the door are lively, moving and expressive of different moods. The designs carved on the body and border of these elephants are alternate hatching, squares, parallel lines and circles (Elwin: 1951:160,161,162). Even elephant in caricature form adorn the Saora door. The lone elephant carved on Bonda door is majestic and symmetrical. (Elwin: 1951:162), The carving of a stag and the head of a cow on the door of two Kondhs at Jantri in Koraput district (Elwin: 1951:166-7) are very lively and bold which could be equated with the palaeolithic paintings of Europe. Particularly the stag is strikingly similar in its presentation to the European palaeolithic art (Peake and Fleure: 1927:89). All the designs either on door, ornament or on other articles could serve various purposes such as training of the apprentices, preparation of decorative pieces for drawing rooms, shelves, dining tables, etc. Since the designs are simple and easy they can help in speedy mass production as well. The continuity of these tribal designs is also traced in the now defunct weights and measures of the tribal and folk use. These objects are found in earthen, brass and wood. The wood is rarely carved, whereas the brass types are elaborately designed and dressed with triangles, hatching, parallel lines, loops, concentric rings, wavy lines, moons, elephants, spirals and cross-lines. The designs seen in the Orissan tribal art are met with in modern products such as handicraft, textile products and in other works. Originating from the chalcolithic or earlier and covering a span of thousands of Kms from Iran to India the culture has found a base in the existing tribal cultural atmosphere. The modern culture is also being influenced by this to enhance its continuity.

Photographs :

References :